Update (9/7/25): An update was issued regarding the origins of the supposed Silk Road drawing.

Two years ago, I wrote an article on historical thinking skills in the classroom after I had read a few books that introduced me to the topic. In my opinion, the article is decent and makes some solid points, but not my best work. This was more an attempt to cement my own understanding of the concepts that I intended to implement in my new history classroom than an authoritative dive into the subject. Since then, I’ve spent countless hours reading the culminations of the past three decades of peer-reviewed research on the topic from industry leaders such as Sam Wineburg, Bruce VanSledright, Peter Seixas, and others; implementing the theories in my classroom; providing professional development for other teachers; and writing a competency-based, historical thinking skills curriculum. At this point, I feel authoritative enough on the topic to share these ideas in a multi-part series that will facilitate teachers in shifting their mindset away from the traditional history class and towards a competency-based, historical thinking skills approach.

Before we begin, let me pose a question: Why study history? This is a question that I’m sure we all pose to our students every year, just like we were asked in grade school. How would you answer? How do you think your students would answer? The most common answers I hear from adults and students alike are something along the lines of “so we can learn from the past” or “so we don’t make the same mistakes again.” In fact, I still remember the poster of George Santayana’s famous quote hanging on the walls of my my 8th grade classroom. Yet unbeknownst to me until fairly recently, many historians actually disagree that you can derive direct lessons from the past. In response to George W. Bush’s fallacious parallels to 1930s appeasement while attempting to drum up support for the Iraq War, British Historian Simon Schama declared, “I’m allergic to lazy historical analogies. History never repeats itself, ever. That’s its murderous charm.”1 Studies conducted by Elizabeth Yeager, Stuart Forster, and Jennifer Greer found that “those students who believe people need history ‘to stop doing the same stupid things’ are likely to oversimplify the past, avoid reference to evidence, and come up with simple historical interpretations of both past and contemporary issues.”2 This is due to the fact that all people, events, and ideas are produced in a certain time and place, with unique, social, political, cultural, and geographic circumstances which change over time. That which applied to a certain temporal space will often have little, if any, direct application to our contemporary world. Therefore, history usually eschews universal laws and generalizations.

Instead, the study of history ultimately boils down to being a better human, member of society, and engaged citizen. Wineburg has frequently argued that the study of history makes us feel more connected to humanity. Learning about people of the past and especially inferring their perspective fosters a sense of belonging to the larger story of humankind. Moreover, history gives us context and understanding of our own times. While we arguably cannot derive directly applicable lessons from the past, we can trace stories and chains of events that helped bring us to where we are today, and we can make meaningful connections and interpretations to contemporary society. This understanding arms us with knowledge that can be used to make the best possible decisions moving forward. To put this another way, how can we determine what to do next if we don’t know how we got here?3 Finally, the discipline of history fosters the development of core inquiry skills required to be an informed, engaged, civic citizen, such as discerning credible information, researching, and creating strong arguments using credible evidence.

The problem with the traditional approach

In The Challenge of Rethinking History Education, VanSledright juxtaposes the teaching styles of two Social Studies educators — Bob Brinton and Nancy Todd — from the same high school. Mr. Brinton is a much-revered veteran teacher who takes a lecture-oriented approach to teaching followed by multiple-choice and matching type tests. He is a powerful storyteller who students often rank as their favorite teacher and whose classes fill up quickly. His version of history can be described as American exceptionalism and hero-worship, especially when it comes to Abraham Lincoln, whom he devotes most of his 12 Civil War lectures to and relying on the students to fill in the missing details of the time period by reading their textbook. Yet students complain that his tests are hard and Mr. Britton himself in turn complains that students don’t do as well as he would like on the tests given how detailed he is in his lectures. Mr. Britton reminds me a lot of my student teaching mentor, a retired Marine Corps officer who has spent the last 25 years assigning textbook sections for homework and giving likely the same PowerPoint lectures about early US History to 8th graders followed by multiple-choice Scantron tests.

Despite decades of historical thinking skills research and implementation in other countries — most notably Britain — this approach continues to dominate Social Studies classrooms in the United States, and it’s not without its significant flaws. First of all, the obvious: in a world with instantaneous access to endless information, what’s the point in making students memorize facts they can Google on their phones in 1.2 seconds flat? This is compounded by the fact that when content memorization is the end goal of the course, students tend to forget most of it shortly thereafter. Not only has this been shown through research, but I have personally seen this in my own classroom; the majority of my students could identify neither when the Civil War occurred nor who the president was only four months after they had learned it at the end of the previous school year. Next, when it comes to the heavy use of fact-based multiple-choice tests for assessment, Wineburg argues that they tell us far more about students’ test-taking abilities than their historical knowledge.4

But most importantly, the traditional Social Studies classroom misses the mark entirely about what it means to do the discipline of history. History is not a giant game of memorization and preparation for a potential Jeopardy! appearance as most students come away believing, but rather a meticulous attempt to piece together arguments about the past using evidence. The arguments, stories, and narratives produced demonstrate historian’s best efforts to reconstruct the past, as opposed to absolute, undeniable certainty about what happened and what it means. Therefore, there is a lot of uncertainty in historical arguments and narratives which fuels debate among historians — debate which is usually lost in the cram and jam of traditional history classes. Furthermore, when students are taught that history revolves around the wholesale absorption and regurgitation of monolithic, pre-packaged, “correct” narratives of the past, they are left vulnerable – even helpless – when exposed to alternative “real” histories which are just as flawed and problematic. To an extent, this may explain the popularity of A People’s History of the United States by Howard Zinn, which has been highly criticized and considered by some to be among the least credible history books of recent times.5

The over-reliance on textbooks poses its own set of problems. Textbooks are typically written in a voiceless, omniscient tone, which implies to the (young) reader that whatever is written is the God’s honest, undeniable truth. Yet textbooks rarely wade into the realm of uncertainty or reveal which sources their information came from. “Many students get their first exposure to history from a textbook. Asked where the book gets its information, children find the question puzzling: the book knows what happened because, well, duh, it’s a history book.”6

Moreover, textbooks often contain information that is false, oversimplified, out of context, or misleading. For example, the passage on Columbus in the high school textbook History of the United States (McDougal-Littell, 1997) is overwhelmingly negative and in some cases, misleading. But one quote in particular stands out as being particularly and verifiably dishonest:

On his first voyage, Columbus had kidnapped several Taino Indians to take to Spain. He had already decided that the Indians “should make good servants” for they were “meek and without knowledge of evil. . . .”

The problem is in the way the author uses the two quotes, both of which come from Columbus’s log of his first voyage. As written, the reader would think the two statements are related and uttered by Columbus in the same breath, and that seems to be what the author wants. However, not only are both statements taken miserably out of context, but they are actually written a month apart — the first from his October 11th/12th entry when first contact was made with the natives and the second from his November 12th entry about why the natives were good candidates for conversion to Christianity.

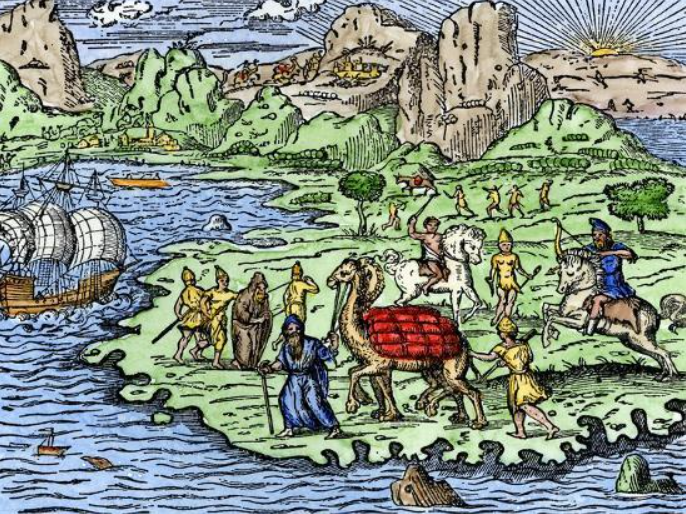

Another example comes from a 4th grade state history book. Examine the picture and accompanying caption.

An astute observer of history would ask some questions here: Who created this source? When? Where? For what purpose? It turns out this drawing originates from Cosmographie Universelle by André Thevet (France, 1575). Not only had the Silk Road ceased operation a century prior, but this picture was not actually “artist’s idea of the Silk Road.” Rather, it was meant to artistically show what he had seen during his travels the Phoenician coast of Syria. In particular, he wanted to represent Mt. Carmel and the Carmelite monastery — which the textbook author cropped off the image! However, a student reading this textbook would know none of that, nor would they necessarily know that they should ask such questions. In addition, and more concerningly, the question in the caption may lead students to believe that those who came before us were ignorant, inferior, or less than, a fallacy that Wineburg and others strongly oppose. It is possible that the author acquired this picture as a stock photo and created the caption without doing research into the original source. This is common practice in many textbooks, especially those geared towards the earlier grades.7

A new approach to teaching history

It is clear that a new approach to teaching history is needed, and thanks to the combination of Wineburg, Seixas, VanSledright, and other scholars too numerous to list, we have just that. Instead of teaching students to memorize information and facts they can instantly Google, the focus becomes the teaching of historical thinking skills. But what are “historical thinking skills”? While the scholarship disagrees somewhat on what the essential historical thinking skills are, there is more agreement on the definition: historical thinking skills encompass the general approach and methods historians use in their quest to reconstruct the past. Wineburg’s research has been particularly productive in delineating what these skills are. His studies involved giving an inquiry question and a set of primary source documents to historians (most of whom specialize in content other than what’s being studied), top Advanced Placement history students, college history students, and even some science and STEM students. Wineburg noticed that all of the historians took the same general approach: they looked at the sourcing information of a document before reading, then annotated, interrogated, read closely, inferred, went back and forth, contextualized, and corroborated the information in the sources to formulate an evidence-based argument. Most of the rest of the participants of these studies skipped some of these steps and usually took the information at face value.

It is these skills that Wineburg and others believe should be the focal point of the new history classroom. This is exactly how Ms. Todd, who teaches across the hall from Mr. Brinton, runs her class. In her classroom, she is not the central figure. Instead, she takes the role of curator, moderator, and guide. Her students are often seen working with primary sources, taking evidence, constructing arguments, and discussing, debating, and defending those arguments.

This has a litany of benefits. Aside from addressing most of the aforementioned problems, teaching historical thinking skills will also develop more transferable, real-life skills than strict memorization. Historical thinking skills are, in many ways, the skills to develop knowledge and learn. In all disciplines and careers, people need to be able to research information and formulate conclusions with factual evidence from trustworthy sources. Determining which sources are trustworthy has become exponentially more difficult in the digital age, and the rampant spread of misinformation attests to how woefully unprepared many adults are to tackle this challenge. As Wineburg has argued on numerous occasions, the future of our democracy largely depends on the ability of the average person to discern information and take informed civic action.

An inquiry-based, historical thinking skills-focused approach is also likely to be more engaging and increase academic stamina, work ethic, and self-direction. It is no secret that long lectures often leave people disengaged and unfocused. This is compounded by the fact that a growing body of research has shown that attention spans are falling, possibly due to increasing amounts of screen time at earlier ages. Yet college term papers and career demands require sustained periods of attention. Immersing students in the inquiry process can not only increase excitement around coursework, but can also develop the work habits and sustained attention required to be successful. The accomplishment of producing a final product after a long inquiry can build confidence in the long run.

Finally, from a big-picture perspective, the universal implementation of historical thinking skills-based courses has the potential to limit the political debates over the minutiae of Social Studies standards that continue to play out nationwide. Instead of worrying about whether we include “Bart Simpson or George Washington,”7 the discussions will revolve around which big-picture, thematic ideas should be investigated. Consequently, this would shorten the curriculum standards and relieve educators from the pressures of content coverage. Additionally, when all sources are presented as “just another source,” imperfect and debatable reconstructions of the past to be scrutinized and critiqued, there may also be fewer discussions over which monolithic narrative will dominate a classroom: this textbook or that one? A People’s History or A Patriot’s History? 1619 Project or 1776 Commission? Students will acquire an understanding that history is far more complicated than an “either/or” story.

Models of historical thinking

Whereas Wineburg observed a general approach to historical inquiry taken by historians, Seixas and VanSledright developed more cohesive and encompassing models of what it means to do history. Both Seixas and VanSledright acknowledge that there is a difference between the “past” and “history”: The “past” constitutes everything that has ever happened; it is vast, infinite, boundless, and often unknowable. “History” is what’s produced when a historian looks at the residue of the past – the fragments, material, sources, or clues left behind – and analyzes, interprets, and pieces together a story or argument about what happened.

In his model, Seixas frames historical investigation through the lens of how historians deal with certain problems or tensions that arise during the process. Those tensions are presented as six concepts: significance, continuity and change over time, perspective, evidence, cause and effect, and the ethical dimension. Since everyone has their own unique paradigm based on education and life experience, how each individual historian navigates those six tensions will influence the choices they make about what to include in narratives or arguments, how to include them, and what it means for the contemporary world. These choices ultimately must be made because the distance between past and present renders it impossible to know or include everything. The result is a narrative about the past, distinctive to the person who wrote it.

As with Seixas, VanSledright’s model starts with a historical question to investigate and results in some kind of argument or narrative, which he refers to as “foreground” or “first-order knowledge.” However, the heart of VanSledright’s model is a cognitive interaction between “strategic/procedural” skills – gathering sources, determining reliability of sources, and taking evidence – and “background/organizing concepts” – historical significance, cause and effect, periodization, contextualization, perspective, etc. To put it another way, history is produced after a back-and-forth interplay between general, inter-disciplinary research and literacy skills and history-specific disciplinary skills. Although he did not describe it as such, Wineburg observed this process with the historians he studied. The historians would go back and forth, visiting and revisiting historical sources, asking questions, seeking answers, and deriving evidence.

In reference to our models above, the traditional classroom tends to focus on the memorization, regurgitation, and discussion of foreground/first-order knowledge. But the Social Studies classroom of the future has students spending more time in the middle, developing and honing the skills used to produce their own foreground knowledge.

Setting up and implementing historical thinking skills in the classroom

By now it should be clear that switching to instruction based on historical thinking skills is the best course of action. But the development of historical thinking skills within a competency-based framework requires different pedagogical methods than instruction that focuses primarily on the memorization and analysis of first-order/foreground knowledge. Below are some general methods for a course focused on historical thinking skills:

- Ensure students understand what they’re learning from the beginning of the course. This is best practice in courses across all subjects, but is indispensable for historical thinking skills based courses. Having become accustomed to traditional, content-knowledge focused history courses, students will tend to equate “learning” with the amount of historical information they are exposed to, memorize, or can discuss. A historical thinking skills focused course will, by nature, expose students to less “coverage” in order to teach skills by delving deeper into select ideas. From the beginning of the course, it is paramount for students to understand that they will be actively engaged in reconstructing the past the way historians do and show their learning by being better able to use these skills over the course of the year – as opposed to reciting increasing amounts of foreground knowledge. Constantly reminding students of this and asking them whether they feel they are better at using these skills is necessary.

- Increase the proficiency level required as the course goes on. It would be unrealistic to expect students to be proficient in any of these skills right away. Thus, the proficiency level required for full credit on an assessment should be lower towards the beginning of year and higher towards the end. This will allow students to receive full credit for making growth along a projected path rather than a static measure of proficiency. For example, if different levels of proficiency are outlined in a five-point rubric, a two may be sufficient for full-credit on an assessment when a skill is first introduced. But as the year progresses and the skills develop, a four or five may be required for full-credit. Furthermore, since the goal of history education is not to develop professional historians, it is unrealistic to expect students to fully master these skills by the time they graduate high school, let alone through a single course. This provides ample opportunity for vertical integration; one course can pick up at the proficiency level that the previous course ended with.

- Keep a student skills portfolio. As previously mentioned, students should know what skills they are going to develop throughout the year. They can keep track of all assignments in which they’ve learned and been assessed on these skills throughout the year, along with how they did on those assignments. This will make it easier for students to visualize and reflect upon their learning progress throughout the course.

- Modeling skills/”Cognitive Apprenticeship”8 approach. An effective approach to modeling skills is the “I do, we do, you do” method. Show the students how to use the skill by doing it in front of them and thinking out loud, then discussing. The second time, invite student involvement in the process of using the skill before allowing them to try it on their own the third time.

- Introduce skills outside of historical context. There is some scholarly debate on this point. Seixas provides examples of decontextualized skill development, such as having students determine and analyze significant events in their own lives to introduce the concept of historical significance. In addition, OER Project World History has a number of activities for introducing skills in a decontextualized manner, such as the “Alphonse the Camel” lesson for introducing historical causation. On the other hand, VanSledright’s views run contrary to this approach, arguing that skills must be developed within the framework of historical inquiry to be meaningful and applicable.

- Isolate the skill being developed in formative work. For example, if students are learning how to establish causal relationships, provide them all of the information necessary and discuss. The benefit of this approach is two-fold. First, if certain information is necessary to facilitate the development of one skill, deficiencies in another skill may hinder that process. Put another way, shortcomings in gathering sources and taking evidence may result in the student not having sufficient information to establish the causal relationship properly. Secondly, if students are trying to do too much at once, they will not be able to develop the desired skill at that time.

- Provide actionable feedback. Ensure students look at the feedback left on formative and summative assessments, so they know what they did well and what they can do better for next time.

- Provide and analyze exemplars. These can be student or teacher made and should provide a model of skills for students to aspire. These exemplars can be analyzed as a whole class or in small groups. Non-desirable assessment examples can also be used as a teaching tool from the perspective of what not to do.

Resources for getting started

Since most teacher preparation programs have yet to train educators in this manner, implementing this curriculum will require history teachers to make a seismic paradigm shift about the focus and end goals of the history course. In order to ensure students are successful, teachers themselves must be proficient in applying these historical thinking skills. Here is a list of books and resources for educators:

- The Challenge of Rethinking History Education, by Bruce VanSledright

- Historical Thinking and Other Unnatural Acts, by Sam Wineburg

- The Big Six: Historical Thinking Concepts, by Peter Seixas and Tom Morton. Can be found online here or downloaded in PDF format here.

- Examining the Evidence – Seven Strategies for Teaching with Primary Sources, by Hilary Mac Austin and Kathleen Thompson

- Why Learn History (When it’s Already on your Phone), by Sam Wineburg

- Inquiry Design Model: Building Inquiries in Social Studies, by Kathy Swan and S.G. Grant

- College, Career, and Civic Life (C3) Framework

- Stanford History Education Group – Reading like a Historian Curriculum and Beyond the Bubble Assessments

Next

Next up in our series will be Part 2: Tips and resources for getting started.

Historical thinking skills in the classroom series

If you enjoyed this article, please follow me on X – @historyinfocus_net. I enjoy corresponding with other educators and those interested in history and economics. Also, you can reach me via the contact page. Please let me know what you thought of this article and how you heard about my website! Thank you!

Endnotes

- Lévesque, Stéphane. Thinking Historically: Educating Students for the Twenty-first Century (p. 59)

- Lévesque (p. 60)

- To demonstrate this point to my students at the beginning of the year, we read a passage about the Czech Crisis and Neville Chamberlain’s invitation to Munich from Rise and Fall of the Third Reich by William L. Shirer. The students are asked a series of questions about what they would do if they were in Chamberlain’s position. Of course, the students are completely lost, because we opened up to a page one-third the way through a 1000+ page book. I then tell my students that we are on page 10,000 of the story of human civilization – how can we possibly write the next chapter if we don’t know what happened before?

- Wineburg, Sam. Why Learn History (When It’s Already on Your Phone), Chapter 6.

- What is the Least Credible History Book in Print? I touch upon the flaws of Zinn’s book in more depth in my articles on Columbus and the 1619 Project.

- Wineburg, Chapter 6.

- Much more on the problem with textbook captions in Examining the Evidence – Seven Strategies for Teaching with Primary Sources, by Hilary Mac Austin and Kathleen Thompson

- This term comes from Reading, Thinking, and Writing About History, by Chauncey Monte-Sano, Susan De La Paz, and Mark Felton.