(Image courteously of Wikimedia commons.)

Attention: If you found this article via a link from a Substack, please use the contact form to let me know where you came from. Thank you!

Let me pose a question: What were you taught about Columbus? Now another one: How many primary or contemporary (to Columbus’s time) sources have you studied extensively? If you’re like me, you may have been taught in grade school that Columbus was a great, courageous hero who sailed into the unknown and discovered America, without which we may not be here today. You may have even had a Columbus Day assembly with a chorus of your fellow schoolmates singing about Columbus sailing the “ocean blue” in 1492. Then, you may have grown up and learned the “real history” about Columbus, that of him being a mass-murdering, mass-enslaving, genocidal maniac who massacred the natives in pursuit of self-enrichment. This was the story that an enlightened young me would tell his guests on his tour bus when it passed the Columbus Monument. This black and white view of the past is a symptom of the way history has often been taught for decades, that of a teacher being “sage on the stage” – the omniscient, authoritative purveyor of a simplified narrative for students to absorb and regurgitate on an assessment. In this style of teaching, primary sources are often an afterthought, if included at all.

My interest in studying Columbus extensively started a few years ago when I was beginning to use an inquiry based approach to teaching history which forced me to seek multiple perspectives and look at the primary sources. Until that point, the extent of my primary source examination consisted of a few popular, highly manipulated or out-of-context quotes highlighted by “experts” with an agenda. When I started looking into the primary source record, it was clear there was far more to the story than what was being put forth. Given the incendiary nature of the topic, I started finding many distortions of the historical record from parties looking to advance their agenda and appeal their cause to the common reader. Finally, I decided once and for all that I would like to know what the historical record says about the matter. As it turns out, when we examine the sources using the methods and techniques of historians and resist simple explanations about Columbus, a rich, complex narrative emerges with plenty of room to debate him and his legacy.

In writing this article, I aim not to convince you one way or the other about Columbus or whether Columbus Day should be changed; it makes no difference to me. Instead, I care about historical truth. I hope to make the case that history is a process of discovery requiring a specific set of skills that yields a nuanced and complicated narrative of the past to be debated and discussed. I will model this process by providing a fairly comprehensive view of what the historical record (primary sources and those written around the time of Columbus) says about him, his voyages, and his legacy, including addressing some of the most saintly accolades and egregious allegations. Moreover, I want to show examples of how people on all sides of the debate distort, manipulate, and falsify the historical record to further their agenda. Ultimately, in doing the former and latter, I want readers to understand the value of engaging in history honestly and the dangers of adopting a single narrative. If I’m lucky, I may even get a few people excited about doing their own history along the way.

But why write about Columbus if I don’t care about him? Columbus makes an intriguing subject of this article for two reasons. First, he’s a controversial figure at the center of an often acrimonious debate taken up by a large portion of Americans every October. Because of this, so many books, polemics, and articles have been written attempting to sway readers one way or the other about his legacy, many using false or misleading claims not backed up by the historical record. But secondly, most of what historians know about Columbus, his voyage, and the pertinent information needed to assess his legacy comes from a small number of primary sources contemporary to him, which are widely available and accessible, sans History of the Indies. Anyone interested can easily read these sources in a relatively short amount of time and come to their own determination.

Sources and methods

The subsequent article is split into four major sections: a brief overview of the world in the 1400s for context, an account and analysis of the events surrounding Columbus’s voyages and contact with natives, an in-depth critique of dominant narratives and allegations of Columbus using primary sources, and an analysis and reflection of the implications of this exercise. Given the controversial nature of the topic, it’s paramount that I do diligence and get it right, or at least as much as a teacher with other obligations can. With that in mind, I rely almost exclusively on primary sources for the account of Columbus’s voyages and the refutations of the narratives. Furthermore, I only use information from primary sources that I am able to acquire in full, and do not use as evidence quotes of primary sources that come from secondary sources. As you will see, most of these are taken out of context and assigned a meaning that may have not existed in the original document. For the context, I use an amalgamation of different primary and secondary sources. It is important to note that while “primary source” in the truest sense of the word means an account from someone who was there, I’m also including sources produced during or close to Columbus’s time, such as Columbus’s biography by his son and the works of Bartolomé de las Casas.

The sources I use extensively are as follows:

- 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus and 1493: Uncovering the New World Columbus Created by Charles C. Mann – two incredible books everyone should read. I use a lot of Mann’s information for context and background.

- History of the Indies by Bartolomé de las Casas, translated by Andrée M. Collard – Las Casas was a friar who came over to the New World in 1502 and became one of the earliest champions of the Indians, giving voice to the oppressed. His works were instrumental in preserving the early history of Spanish contact with Indians by creating a manuscript of Columbus’s first voyage log (the original no longer exists), and writing History of the Indies and Brief Account of the Destruction of the Indies, the latter of which was written primarily about Spanish atrocities committed after Columbus’s time. This version of History of the Indies is the only one in English, and only select chapters are translated. This makes it challenging to use as a source, since it does not provide a full or contiguous narrative. Regardless, the book is rare and I was lucky enough to come across a copy at a local college library. For the purpose of taking evidence, it is important to note Las Casas’s penchant towards the Indians’ cause.

- The Diario of Christopher Columbus’s First Voyage to America 1492-1493, abstracted by Fray Bartolomé de las Casas, transcribed and translated into English by Oliver Dunn and James E. Kelley, Jr. – as stated above, the original journal no longer exists, and we have this one thanks to Las Casas. It is important to note that this log was written for the purpose of presenting to the king and queen of Castile, and the information in it needs to be examined with that in mind. It is also important to note that there are multiple translations of the log, and they may have stark differences in wording. I like this version because it has the original Spanish alongside the English translation.

- Various letters and documents written by Christopher Columbus

- The Life of the Admiral Christopher Columbus by his son Ferdinand Columbus – an account of Columbus’s life based closely on primary sources of the time, including Columbus’s lost second voyage log. Las Casas relies heavily on this in writing History of the Indies. It’s important to keep in mind the author and his possible purpose of clearing his father’s name.

- Michele de Cuneo’s Letter on the Second Voyage, 28 October, 1495 – Cuneo was a friend of Columbus’s who accompanied him on his second voyage. This letter was written to a friend upon returning home, and provides a raw, non-sanitized look into daily life with Columbus. The link provided is only part of the letter. I relied on Christopher Columbus and the Enterprise of the Indies: A Brief History with Documents by Geoffrey Symcox and Blair Sullivan (2005) for the full version.

- Dr. Diego Alvarez Chanca’s Letter on the Second Voyage, 1494 – Dr. Chanca was a physician for the king and queen of Spain, and was appointed by them to accompany Columbus on his second voyage. Given Chanca’s position as physician and detailed descriptions, he provides possibly the best evidence for the existence of cannibalism by the Caribbean Indians, but that needs to be weighed with the fact that the letter was written for the Court of Castile.

Among the challenges of researching Columbus is the fact that most of these sources were originally written in Spanish, and translations differ. Furthermore, these sources were written almost 500 years ago, and one cannot assume that words have the same meaning or connotation as they do today, which sometimes make deciphering and determining meaning of passages difficult. In such cases, I have done my best to cross-reference and corroborate from different sources.

One final note: given that the term “Indian” is the one most commonly used in the primary sources and in Mann’s books, I will be using it in the article to refer to the natives, despite the word being technically incorrect. Mann reasons that using the term “Indian” would clear up confusion, and furthermore explains that he refers “to people by the names they call themselves. The overwhelming majority of the indigenous peoples whom [Mann has] met in both North and South America describe themselves as Indians” (1491, p. xi). This was true when I recently visited the Cherokee Indian Reservation in North Carolina.

Context: The world of Columbus

Contextualization is a skill historians use that involves analyzing events, attitudes, and institutions of the time and place surrounding a topic of interest, along with analyzing sources in full. By getting a sense of what the world was like, historians can avoid presentism – the evaluation of historical events through present cultural values and norms. In the pursuit of an accurate interpretation of Columbus and his legacy, it’s important we first look at the global landscape of his era.

In order to get a complete perspective, we need to imagine a world much different than ours with a zeitgeist unfathomable to most modern day persons. So different was the world, in fact, that almost any area in the world today would look more familiar to us than Europe during the time of Columbus. As you read the following, try to put yourself in the mindset of the time.

Modern technology as we know it didn’t exist, since this was prior to the scientific revolution. Most people in Europe and other parts of the world still believed the Ptolemaic view of the Earth as the center of the universe; the Church, which was the highest authority of the land, forbade any thoughts to the contrary. Andreas Vesalius – the founder of modern human anatomy – whose life’s work produced a comprehensive view of the workings of the human body, had not been born yet. Sickness was seen as an imbalance of “humors” and often treated with some form of bloodletting, since there would be no knowledge or even hypothesis of the existence of microorganisms for centuries to follow. Alchemists, who were in some ways the antecedents to modern chemists, tried earnestly to turn common materials into gold. Most unknowns were answered by the realm of religion.

The means of transportation were primitive, with the only options being foot, horse or other animal, or ship. Most people lived their whole lives without a broad concept of where they were in the world and without venturing far outside their village, where most of the world’s population worked in agriculture. The average peasant had little to no awareness of different people and cultures. Those who needed to communicate long distances may have to wait weeks for responses. Even the most learned of the time had a primitive view of the planet, as evidenced by this world map created in late 15th century Germany by Henricus Martellus Germanus. The residents of the Americas also had no knowledge of a world beyond their regions, let alone across vast oceans.

Daily life was hard on most Europeans. The average life expectancy was between 30-40 years old, although this is skewed due to infant mortality rates. As stated, most Europeans still worked in agriculture and made low wages, even after the upheaval of Black Death a century before. Economically, we start to see the beginnings of a proto-market economy, but one in which kings believed wealth was measured by the amount of gold and silver in the government’s coffers. The average family had very few material possessions. Though the Renaissance was in full swing in parts of Europe, many historians have pointed out that this mainly impacted the lives of urban elites, leaving most completely unaffected. Absolute monarchs were starting to coalesce power in Europe, causing competition between states, but commoners often felt little connection to the king. The Pope was still the top authority in Europe, and religion dominated many facets of life.

Large kingdoms and empires existed in all parts of the world. The Triple Alliance (Aztecs), Mayas, and Incas in the Americas had large, populous cities with advanced engineering, technology, arts, and culture. The wealthy African kingdom of Mali, where Mansa Musa made his famous journey to Mecca a century and a half earlier, was giving way to an even more powerful Songhai kingdom. Other African kingdoms became wealthy through vast trade networks that linked them with the Middle East, India, and China. China was the wealthiest and most populous empire of the age, whose riches captivated the European imagination ever since Marco Polo’s journeys two centuries prior. The Ming Dynasty sought to expand political power across India and Africa by sending large treasure fleets under the admiral Zheng He to traverse the Indian Ocean.

In 1453, The Ottoman Empire put the final nail in the coffin of the millennium-old Byzantine Empire by taking Constantinople and cutting off Europe from the Silk Road and the riches of China that came with it. This provided a significant impetus for the Europeans to seek sea routes directly to Asia. For decades prior to this, the Portuguese had already been training mariners under Prince Henry the Navigator to explore the coast of Africa for riches. By the time Columbus sailed to the New World, Portuguese mariners had rounded the southern tip of Africa.

Violence and brutality were facts of everyday life in societies across the world. The Spanish Inquisition had replaced the Medieval Inquisition, meting out gruesome, imaginative forms of a torture upon Jews and other heretics. Being burned at the stake had long been a common means of execution for enemies of the church.

Warfare was common and captives were often treated in ways which would horrify modern sensibilities. Of particular interest to the subsequent article is that of the people of North and South America, who are often portrayed wrongly in history books as peaceful, proto-communistic societies. The Triple Alliance (Aztecs) was a large empire that was in the process of expanding by conquering neighboring peoples, largely with the goal of acquiring victims for ritual human sacrifice, which they practiced en masse (1491, p. 133).1 So much so was the discontent among the oppressed that conquistador Hernán Cortés was able to rally upwards of 200,000 Indians to ally with his meager force of Spaniards and bring the downfall of Tenochtitlan, the capital city with around 200,000 residents.

Further to the south, the Incas of the Andes had been building a 2,500 mile long empire for almost a century, conquering and subjugating people of the region. When European diseases (which preceded first contact with the Spaniards) found the empire, it fractured and fell into a brutal civil war. According to Mann, one battle resulted in 16,000 dead while another had a death toll estimated at 35,000. It was in this battle that Atawallpa (the Inca who would confront Francisco Pizarro four years later) captured the rival Inca, and “executed his wives, children, and relatives in front of him.” (1491, p. 88)

In the Caribbean where Columbus landed, evidence abounded of conflict (which will be detailed later), yet how frequently it occurred is up for debate. Columbus and the people who accompanied him wrote on multiple occassions that the Indians were afraid of being taken captive by potentially cannibalistic rival tribes who would sometimes castrate or keep them as concubines.

Slavery was a fact of life for most societies in the world, in a way that’s hard for us to imagine today. In particular when referring to the trade of slaves in Europe and Africa, Mann explains that “few Europeans or Africans at this time viewed slavery as an institution that needed to be explained, still less as an evil to be decried. Slavery was part of the furniture of everyday life; in both Europe and Africa, depriving others of their liberty wasn’t morally problematic.” (1493, p. 443) Indeed there had existed for centuries a vast African slave trading network prior to European involvement. To explain why, Mann cites Harvard Historian John Thornton: “slaves were the only form of private, revenue-producing property recognized in African law.” (1493, p. 443) Thus it was that kings in Africa would gain great status and wealth by trading slaves to the Middle East and Asia. The demand for slaves grew upon entry of the Portuguese in the mid-1400s, and the kingdoms were happy to provide.

Even in the Americas, slavery was common. In reference to the societies of North America, Mann writes that the institution occurred in “most Indian societies,” but differed by region. In northern Powhatan societies, “Slaves were prisoners of war who were treated as servants until they were either tortured and slain, ransomed back to their original groups, or inducted into Powhatan society as full members.” (1493, p. 142) On the contrary, in the Muskogean confederacies of the south, “War captives also became slaves . . . Slaves worked in fields, performed menial tasks, and could be given away as gifts; female slaves provided sexual services to honored male visitors (a gesture frequently misunderstood by Europeans, who thought that the Indians were offering their wives).” (1493, p. 142)

A brief account of Columbus’s voyages

Columbus sailed on his famous westward voyage on August 3rd, 1492, with three caravels and 85 men. Approximately 10 weeks later, after traveling farther than anticipated and holding his crews together in the face of potential mutiny, he landed on an island in the Bahamas that he named San Salvador. But just getting the backing for this voyage was a challenge for the Genoese native born to a humble family in a bustling hub of trade and mercantilism.

Seeking to capitalize on the European attempts to find a sea route to Asia, Columbus first attempted to get the backing of King João II of Portugal for his unprecedented idea of sailing westward. After three years of trying, he was ultimately turned down. Portugal already had lucrative ventures in Africa that netted riches – gold, slaves, and spices. Moreover, aside from being unnecessary for the Portuguese, Columbus’s proposal was risky. No one had ever reached Asia by sailing westward from Europe, and Columbus’s estimate of the earth’s circumference (18,000 miles) was less than the true distance of over 24,000 miles which had been calculated by Greek astronomer Eratosthenes 1500 years before.

Columbus then made his way to Spain in 1485. However, unlike the Portuguese who had defeated the Moorish Muslims 200 years before, the Spanish crown was embroiled in the nine-year long Siege of Granada, the final campaign of the centuries long Reconquista. Preoccupied with war, King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella were unable to fund the voyage. This changed in January of 1492, when the Moors were defeated and removed from the Iberian peninsula. Consequently, resources were freed and the monarchs saw an opportunity to catch up to the Portuguese in exploration and colonization. The agreement was such that Columbus would be given approximately 1.1 million maravedis, with the other 600,000 provided by Columbus himself (a total of approximately $530,000 today2) to outfit his voyage. Furthermore, he would be given the title “Admiral of the Ocean Sea,” made governor of all lands he discovered for the crown, and be allowed to keep one tenth of all riches acquired.

Upon landing on San Salvador, Columbus took the island for the king and queen of Spain and made contact with the natives. Relations were amiable at first. Columbus writes:

“In order that they would be friendly to us – because I recognized that they were people who would be better freed [from error] and converted to our Holy Faith by love than by force – to some of them I gave red caps, and glass beads . . . and many other small things of value, in which they took so much pleasure and became so much our friends that it was a marvel.” (Diario, p. 65)

The Indians returned the favor, giving all they had. Columbus’s words show the importance placed on converting the Indians to Christianity, and this appears innumerable times throughout his correspondences and journals, including later in the entry when he says “I believe that they would become Christians very easily, for it seemed to me that they had no religion.” (Diario, p. 69) So too are the first attempts to find gold, one of the principal objectives of the voyage, mentioned first in his entry two days later.”I was attentive and labored to find out if there was any gold; and I saw that some of them wore a little piece. . . . And by signs I was able to understand that, going to the south . . . there was there a king who had . . . very much gold. . . . And so I will go to the southwest to seek gold and precious stones.” (Diaro, Saturday, October 13th, p. 71)

After taking some Indians captive to bring back to Spain, learn the language, and serve as interpreters (a practice he learned from the Portuguese exploration of Africa, as he writes in his November 12th entry [Diario, p. 147]), Columbus continues to explore the islands. In the process, he pursues a primitive strategy of winning hearts and minds that involves capturing the natives, giving them gifts, and then releasing them. We see this play out over and over, and Columbus explains in his December 12th journal entry: “I had ordered them to catch some [people] in order to treat them courteously and make them lose their fear.” (Diario, p. 219) Columbus had heard rumors from the Indians that there was a land of one-eyed cannibals, and since the captives didn’t return, the Indians presumed they had been eaten. (Diario, p. 167) Columbus further writes, “those people must be much hunted since they live in so much fear and because, just as soon as we arrive anywhere, they make smoke signals from the lookouts throughout the land.” (Diario, December 15th, p. 229)

Columbus and his men continue on to the island of Cuba, which he believes is the main continent, and then to the island of Hispaniola, supposedly housing large deposits of gold. There he befriends a Taíno cacique (a king or leader in their language) named Guacanagarí, whose people supposedly believe the Spaniards came from heaven.

Columbus’s challenges began to mount when, in a portent of events to come on subsequent voyages, his caravel Pinta disappeared for six weeks, and Columbus believed they had gone without him to seek riches. On top of that, the Santa Maria shipwrecked off the coast of Hispaniola on Christmas. Hearing from the friendly cacique that there were large deposits of gold on the island, Columbus’s men used the wood salvaged from the wrecked caravel to build the first settlement in the New World, aptly named La Navidad. 36 men were left in the fort while Columbus sailed back to Spain.

On the way, his men had their first skirmish with a group of Indians. The January 13th entry states that Columbus’s men pulled up to a shore while the Indians instructed their peers to leave their weapons behind. Then “the Spaniards began to buy from them bows and arrows and other arms, because the Admiral had so ordered. When two bows were sold, they did not want to give more; instead, they prepared to attack the Christians and capture them. . . . Seeing them come running toward them, the Crhistians, being forewarned . . . attacked the Indians. And they gave one Indian a great blow with a sword on the buttocks and another they wounded in the chest with a crossbow.” The Indians then fled. (Diario, p. 333)

Columbus returned to Spain with a hero’s welcome, parade and all. A second voyage was promised by the monarchs, and sailed on September 25th, 1493, with 17 ships and 1200 men. The goal for the king and queen was colonization. On November 2nd, Columbus’s fleet arrived in the modern day Lesser Antilles Islands, home of a supposedly cannibalistic tribe called the Caribs that Columbus and his men heard so much about on the first voyage. The Spaniards found Indians who were taken captive from other islands by the Caribs and took them on their ships after they begged to go. (The Life, p. 113)

At this part of the narrative, there exist from multiple sources (Ferdinand Columbus, Dr. Chanca, Michele de Cuneo, etc) numerous and vivid descriptions of captive Indians talking about how the Caribs raid other lands, take women as slaves, and eat the men. Dr. Chanca writes, “In their wars upon the inhabitants of the neighboring islands, these people capture as many of the women as they can, especially those who are young and handsome, and keep them as body servants and concubines.” (Chanca, p. 442) Furthermore, Chanca describes evidence of cannibalism: “of the human bones we found in their houses, every thing that could be gnawed had already been gnawed, so that nothing else remained of them but what was too hard to be eaten. In one of the houses we found the neck of a man undergoing the process of cooking in a pot, preparatory for eating it.” (Chanca, p. 440)

It is important to note that there is a debate among historians as to the extent of which, if any, cannibalism was actually practiced in the Caribbean. Some claim this was significantly exaggerated or wholly fabricated by Europeans of the time to justify the oppression and enslaving of certain groups of Indians, while others give more credence to these accounts.

What seems less disputable, however, is the practice of genital mutilation performed by the Caribs upon their captives. During those initial encounters, Dr. Chanca writes, “When the Caribbees take any boys as prisoners of war, they remove their organs . . . Three boys thus mutilated came fleeing to us when we visited the houses.” (Chanca, p. 442) This is corroborated by Cuneo who writes that they took two teenage boys who “had the genital organ cut to the belly; and this we thought had been done in order to prevent them from meddling with their wives or maybe to fatten them up and later eat them.” We see this explained again after a skirmish with a canoe of Caribs left a Spaniard dead. The Caribs had with them two captives (referred to as “slaves” by Cuneo) “of whom (that is the way the Caribs treat their other neighbors in those other islands), they had recently cut the genital organ to the belly, so that they were still sore.” (Cuneo) Ferdinand Columbus writes of the incident, “These men had had their virile members cut off, for the Caribs capture them on the other islands and castrate them, as we do to fatten capons, to improve their taste.” (The Life, p. 117) Las Casas corroborates this description. (History, Book I, Ch. 85, p. 45)

Columbus sailed from the Carib islands to Hispaniola, exploring San Juan Bautista (presently Puerto Rico) on the way. Upon arrival, he received sobering news that all of the Christians had been killed. According to the Indians, “soon after the Admiral’s departure those men began to quarrel among themselves, each taking as many women and as much gold as he could. [Ten Spaniards] left with their women for the country of cacique named Caonabó, who was lord of the mines. Caonabó killed them.” (The Life, p. 119) Shortly thereafter, Caonabó and his men marched on La Navidad, burning the settlement and killing the Spaniards who fled. Guacanagarí, along with his men, had helped defend the Christians, but fled when he was wounded. The Admiral met with the wounded cacique, who turned out to be faking the injury. (Chanca, p. 441) Since the Spaniards depended heavily on the Indians for food and provisions, they had to hide their distrust. This ordeal is the first of many where Columbus’s men would wreak havoc on the Indians in his absence.

Columbus, who had been ill for some time, left Navidad and founded a new settlement named La Isabela – the first permanent European settlement in the New World. This was not far from where he was told by Indians that there were gold mines. There had recently been a mutiny by Spaniards who were eager to “load themselves with gold and return home rich.” However, “they did not know that gold may never be had without the sacrifice of time, toil, and privations,” (The Life, p. 122) so they conspired to seize some ships and return home. The mutiny was discovered and squashed.

A small expedition under Alonso de Hojeda found gold mines in the Cibao region, and Columbus had his men build the fort of Santo Tomás nearby. In an incendiary incident involving a force sent to relieve the fort in April of 1494, the Indians helping the Spaniards ford a stream ran away with their clothing, and the cacique had taken some for himself. In response, Hojeda, who had already chained one cacique, cut off the ears of an Indian subject and brought him, the cacique, and some of the cacique’s relatives to the Admiral. Initially, Columbus sentenced them to death for their insubordination, but pardoned them after pleas from another cacique. Las Casas condemned the show of force: “The admiral should have taken pains to bring love and peace and avoid scandalous incidents, for not to perturb the innocent is a precept of evangelical law whose messenger he was. Instead, he inspired fear and displayed power, declared war and violated a jurisdiction that was not his but the Indians’.” (History, Book I, Ch. 93, p. 52-3) Shortly thereafter, Columbus appointed a council to govern the island so he could explore Cuba and Jamaica – a journey of five months.

In the Admiral’s absence, rule and order fell apart once again. One of his leaders, Pedro Margarit, whose mission it was to defend against a potential insurrection and establish peaceful relations in the Vega Real region near Cibao, attempted to take control of the island for himself, and fled to Spain upon failing to do so. Leaderless, the Spaniards previously under his control “went where [they] willed among the Indians, stealing their property and wives and inflicting so many injuries upon them that the Indians resolved to avenge themselves on any that they found alone or in small groups.” (The Life, p. 147) Revenge was taken when a cacique named Guatiganá killed 10 Christians and burned a hut full of 40 sick men. In response, Columbus had 1600 of the caciques subjects rounded up, 500 of which were sent back to Spain as slaves (more on this later).

In an attempt to put down the full scale rebellion, Columbus “punished six or seven others who hard harmed Christians.” (The Life, p. 148) The four highest caciques of the island thus unified against the Christians, but Guacanagarí remained an ally of Columbus. The cacique explained how he had supplied the Spaniards, drawing the ire of the other chiefs. One of them, Behechio, killed one of Guacanagarí’s wives, while Caonabó stole another. The combined army of Columbus and Guacanagarí met 5,000 rebel Indians in battle3 and scattered them with a pincer maneuver using harquebus shots, cavalry, crossbows, and hounds. The “Indians fled in all directions, hotly pursued by our men, who . . . soon gained a complete victory, killing many Indians and capturing others who were also killed. Caonabó . . . was taken alive together with his wives and children.” (The Life, p. 149) The captive cacique confessed to killing 20 Christians at Navidad and doing reconnaissance at Isabela, hoping to repeat the feat. He was sent to Spain with one of his brothers as prisoners, but did not survive the voyage. Assisting Columbus and his men in this conquest was disease, which killed two-thirds of the Indians.

To keep the Taínos subdued, Columbus implemented a tribute system. In Cibao, the region with the gold mines, “every person fourteen years of age or upward was to pay a large hawk’s bell of gold dust,” while “all others were each to pay twenty-five pounds of cotton.” (The Life, p. 149-50) Those who didn’t pay were punished, but there is no evidence in the historical record as to what that punishment was (more on this later). Leaving his brother Bartholomé in charge of the island, Columbus sailed back to Spain.

A third voyage was planned for Columbus, but not with the haste of the second. The crown of Castile was preoccupied with other foreign affairs, and rumors of the deteriorating conditions in the Indies and lack of substantial return on investment led the king and queen to drag their feet. Nonetheless, Columbus’s third voyage was approved with the main goals of resupplying settlers and exploring the land of “Paria,” present day Brazil. It is important to note that the eagerness shown by participants of the first two voyages was now absent, prompting the crown to fill the ships with criminals.

The fleet set sail in earnest on May 30th, 1498, reaching the island of Trinidad in late July, and sailing towards the mainland. Columbus became the first European to explore South America, though Amerigo Vespucci later falsified the date of his 1499 expedition in his log, claiming it took place in 1497. This error is the reason the continents bear his name instead of Columbus’s. (History, Book I, Ch. 163, p. 62) Aside from a minor skirmish stemming from a misunderstanding, relations with the Indians were amiable and gifts were exchanged frequently. Columbus and his crew found evidence of gold, pearls, and other riches. Having explored the mainland, the fleet set sail towards Hispaniola to resupply the settlers.

When the Admiral arrived, he found the island in a decrepit state of affairs. The longer than anticipated absence led to discontent as provisions ran low and strict rules wore away their patience. As was stated multiple times by Ferdinand Columbus and Las Casas, most of the Spanish who came on the voyages believed they would find quick riches and be able to return to Spain, becoming fast discontented when this didn’t happen. Francisco Roldán, mayor of La Isabela, took advantage of this discord to foment rebellion against the colonial administration. Roldán enticed rebels with the idea that “all the wealth of the island should be equally divided among them, and they should be allowed to use the Indians as they pleased, free from interference, whereas now they might not even take for themselves any Indian woman they pleased.” (The Life, p. 192) The Adelantado (governor), Bartolomé Columbus, ruled with an iron fist over the settlers, enforced the three monastic vows,4 and “imposed fasts and floggings, jailings and chastisements, and that for the most trivial fault.” (The Life, p. 193)

The original plan of Roldán was to sow discord and take over the governorship of the island for himself, killing the Adelantado if he had to. When those plans fell through, he rallied some Indian allies under the cacique Guarionex to help him attack and seize the mining town of Concepción. This too failed when one of the subordinate caciques attempted to take the town for himself, revealing the plan. This cacique was put to death by Guarionex. After Columbus arrived with supplies, he was able to reach an agreement to end the rebellion, which included providing Roldán supplies, slaves, and protection in exchange for his loyalty.

However, the agreement did not end the strife on Hispaniola. As Columbus was planning to leave for Castile, Hojeda arrived and spread rumors about the queen’s imminent death to undermine the Admiral – who had the backing of the monarch – and convince his enemy, Bishop Fonseca, to do something about Columbus. This set off a new civil war between Hojeda and Roldán, which, in addition to the multitude of complaints about the tyranny of the Columbus brothers from settlers (some justified, others exaggerated), prompted the monarchs to send Francisco de Bobadilla to the island to relieve Columbus of his governorship. Columbus and his brothers were arrested and brought back to Spain in 1500. Though Columbus was eventually pardoned and provided the backing for a fourth voyage, this effectively ended his governorship and influence in the New World.

Analysis and takeaways

Columbus’s first voyage established fairly peaceful relations with the Indians he encountered. His strategy of catch, treat well, and release in order to win hearts and minds seemed to be working early on. On multiple occasions, he writes in his log how fleeing Indians were turned around by interpreters who told them that the Spaniards were good people. It is likely that Columbus believed it would be much easier to find gold and convert the Indians to Christianity if he established peaceful, trustworthy relationships. He befriended the cacique Guacanagarí, who may have seen the Spanish as a powerful ally against attack from the warlike tribes that Columbus had heard so much about.

The Admiral never lost sight of his goal. On every new island he came to, he inquired about where the gold was. In this pursuit, following the precedent set by the Portuguese, he would take a few natives from each island (often against their will) to serve as interpreters so that they could guide him to gold. It is likely that he had the intention of returning most, as peaceful relations were paramount. However, he showed his willingness to skirmish with the Indians in order to defend the Spanish. It is important to note that regarding this incident, Las Casas wrote: “[Columbus] says that he wishes to depart because now there is no benefit in staying because of those difficulties with (he should say their shameful conduct toward) the Indians.” (Diario, p. 337-9) This shows that Las Casas may not have believed the Spanish were acting in self defense.

Whereas Columbus’s first voyage ended amiably in terms of relations with the Indians, things began to unravel thereafter, starting with the debacle of La Navidad. Time and time again we see Columbus’s failure to keep order with the common men and leaders below him, along with his constant need to defend against mutiny. So much so was the effort to undermine Columbus that a group of noblemen went back to Spain and told the monarchs that the enterprise in the Indies was a “joke” since there was no gold to be found (despite the ample proof provided by Columbus). (History, Book I, Ch. 107, p. 56) Though Columbus had shown his desire to set up gristmills and establish long-term agriculture in the towns on Hispaniola, the settlers had little interest in working for themselves. In response, the Admiral used an iron fist to force work, drawing the ire of the hidalgos (Spanish gentleman class). “The admiral had to use violence, threats and constraint to have the work done at all. As might be expected, the outcome was hatred for the admiral, and this is the source of his reputation in Spain as a cruel man hateful to all Spaniards, a man unfit to rule.” (History, Book I, Ch. 92, p. 49) Furthermore, the behavior of the Spaniards towards the natives fed violent resistance and forced Columbus to take brutal measures of subjugation, including rounding up Indians to be sent back as slaves, ordering executions, and implementing the tribute system.

Curious throughout the second voyage is the behavior of Guacanagarí. He relates his story of defending the Christians to some Spaniards who visited the village, citing his injury as the reason he’s unable to see the Admiral. Ultimately, he does see Columbus, and they find out he’s faking the injury. The next time Guacanagarí is mentioned is on April 24th, 1494, when “at the sight of the ships [of Columbus], he fled in fear, though his people pretended that he would soon return.” (The Life, p. 131) This shows evidence of a potential strain in the relationship between the cacique and the Admiral. When Guacanagarí meets Columbus again to ally in the war, he does so to retrieve his wife from Caonabó. To win over the Admiral, the cacique seeks him out upon hearing of his return, reminds him of his hospitality, and weeps whenever the dead of Navidad are mentioned. (The Life, p. 148) This may have been an act to ensure he could count on using the Spaniards’ support as needed.

When Columbus left for Spain, he appointed his brother as governor. There is evidence that the Adelantado ruled tyrannically in the Admiral’s absence – meting out harsh punishments to Indians and Spanish alike. On one occasion, Don Bartholomew had a few Indians burned at the stake for destroying Christian images – a common punishment for heresy in Europe. This led to retaliations. By the time Columbus returned on his third voyage, conditions had deteriorated so completely that he was unable to regain control, playing a significant role in his being brought back to Castile in chains.

The complex set of events and circumstances makes assessing Columbus and his legacy challenging. On one hand, he set out to do something that no other known European at the time had done. He showed enormous courage, bravery, and seamanship – “the most outstanding sailor in the world” executing “the most outstanding feat ever accomplished . . . until now” per Las Casas (History, Book I, Ch. 3, p. 17) – in finding the New World, and his pacification strategy seemed to be working at first. However, the role of luck in this achievement cannot be understated. Had there not been a continent in his way, his underestimation of the earth’s circumference would have undoubtedly resulted in the deaths of him and his crew. Furthermore, his limitations as a governor and proprietor of permanent settlement became apparent in the second voyage, along with his ability to levy harsh punishments.

Las Casas himself had conflicted emotions about Columbus, which is detailed here.5 To add to that, he thought that Columbus had done a deed to the whole world and all of Christendom:

“Many is the time I have wished that God would again inspire me and that I had Cicero’s gift of eloquence to extol the indescribable service to God and to the whole world which Christopher Columbus rendered at the cost of such pain and dangers, such skill and expertise, when he so courageously discovered the New World. . . . Is there anything on earth comparable to opening the tightly shut doors of an ocean that no one dared enter before? And supposing someone in the most remote past did enter, the feat was so utterly forgotten as to make Columbus’s discovery as arduous as if it had been the first time.” (History, Book I, Ch. 76, p. 34-5)

The prophetic comment about someone else finding the Americas first is significant here and is one of the key points in the current debate about Columbus. Las Casas did not know about Lief Erikson’s expeditions to Newfoundland, but preemptively made the point about how it wouldn’t matter since Europe did not know of the Americas prior to Columbus’s voyage.

On the other hand, Las Casas didn’t shy away from indicting Columbus for ill treatment of the natives. He questions the actions of the Admiral in fighting the war against Caonabó: “Did the admiral and Adelantado fight a just war against them by any chance? And what of sending slave ships to Castile? And putting iron chains on the two major kings of this island, Caonabó . . . and Guarionex . . ., causing them to drown at sea?” (History, Book II, Ch. 11, p. 104) Moreover, he faults Columbus for having tolerated a labor system under Roldán in order to suppress his insurrection. “This is how the comendador mayor imitated the practice [of forced Indian labor] which Francisco Roldán had initiated, which Columbus had tolerated and Bobadilla had developed by allowing his Spaniards free use of Indian labor for building and maintenance work.” (History, Book II, Ch. 10, p. 102)

Was Columbus guilty of Genocide? It doesn’t seem that way. Indeed a genocide was committed against the Indians, and Columbus set off a chain of events that led to ultimately the destruction of the people. But the destruction of the Indians as a group came at the brutal hands of those who followed Columbus, and scholars generally agree that most Indians in the Americas were wiped out by Old World diseases. (1493, p. 32) Columbus was “unjust” and “oppressive” in his treatment towards the Indians per Las Casas, but his actions did not directly cause their destruction, nor was that his intent. He would have preferred to live peacefully with the Indians as subjects of the Spanish crown. Furthermore, historical context is important here. Few if any of Columbus’s actions were unique for the time period.

Columbus: hero, civil rights activist, defender of Indians?

While the most common and prominent voices in the debate about Columbus lean toward highlighting the negative aspects of his legacy, there still exists a vocal contingency who view him as a hero and a defender of Indians. These include Puerto Rican born Rafael Ortiz, author of Christopher Columbus The Hero: Defending Columbus From Modern Day Revisionism, and Philadelphia civil rights attorney and “Columbus expert,” Robert Petrone. Petrone’s “1492 Project” series of articles in particular portrays Columbus as a civil rights activist, and he even produced a sanitized report on History of the Indies to the city of Philadelphia in attempt to prevent them from removing the Columbus Memorial. But while it is likely Columbus did have some genuine affection for the Indians, especially at first (this comes across in his writings), any altruistic motives in “rescuing” (Petrone’s words) Indians from the Caribs were tertiary to the main objective of obtaining gold and Christian souls.

Since one of the goals of my writing is to show the tactics writers use – in this case, both proponents and detractors of Columbus – to cherry-pick, manipulate, distort, misrepresent, and omit historical evidence in order to convince others of the validity of their version of history, I will rely heavily on Petrone’s articles (mainly the one about the second voyage) in this section, since they are more accessible than Ortiz’s books. Furthermore, since Petrone is not a historian by trade, his writings show the lack of certain historical thinking skills employed by professionals. He takes information from sources at face-value without question, resulting in suspect claims and further strengthening the argument that such skills need to be taught in school.

Petrone begins his second voyage narrative (Part V in his series) by claiming multiple times that the Indian interpreters who accompanied Columbus back to Spain were “eager” and “willing” to go. However, by Columbus’s own admission, this was not always the case. In his October 15th log entry from the first voyage (only four days after first landfall), he writes, “And close to sundown I anchored near the said cape in order to find out if there was gold there, because these men that I have had taken on the island of San Salvador kept telling me that there they wear very large bracelets of gold . . . I well believe that all they were saying was a ruse in order to flee.” (Diario, p. 79) Moreover, in a letter to Luis de St. Angel (treasurer of Aragon) following the voyage, Columbus states, “Directly I reached the Indies in the first isle I discovered, I took by force some of the natives, that from them we might gain some information of what there was in these parts.” He would continue to do this on many islands he came to. Finally, an exercise in historical empathy would reveal that even though the Indians may have thought the Spaniards were men from Heaven, it’s highly unlikely that they would have willingly left their homes to go with them at first sight.

As Petrone continues his narrative, he describes Columbus’s actions in rescuing captive Indians from the Caribs as being akin to Harriet Tubman’s Underground Railroad. However, this is a questionable interpretation. After learning he was in the Carib Islands from a native that was taken, he encountered a group of six women who had fled from the Caribs and wanted to come on the ship. Columbus resisted at first, “not wanting to anger the people of the island,” (The Lilfe, p. 113) but finally relented after their pleas. I was also unable to find any mention of Columbus and his men returning these people to their home islands, but Cuneo does mention sending to Spain “as samples” some of the captives who had been castrated by the Caribs. To me, this further shows Columbus’s primary motive of attempting to keep peace in order to find gold. He may have determined that the services rendered by these grateful refugees would outweigh any offense to the islanders.

In describing the Navidad incident, Petrone shows that he either does not understand the circumstances surrounding the events, or a willful misrepresentation of the sources. His description of an attack and murder in “cold blood” by “the Carib high-king” Caonabó, both ommits mention of Spanish provocations that caused the retaliation and falsely claims the cacique was Carib, and thus a cannibal. Caonabó, along with all the tribes of the island of Hispaniola, were Taíno, yet Petrone continues throughout the article to push the false, simplistic narrative of Taíno (friendlies) vs. evil cannibalistic Caribs. He takes at face value all of the claims of cannibalism, unaware of or uninterested in the scholarly debate surrounding it. In a later article, he claims that Columbus “forged lifelong friendships with Taíno chieftains,” but the record shows that the majority of the caciques were united against him. In fact, when Juan Aguado was sent to by the monarchs in 1495 to assess the situation on Hispaniola, Las Casas writes that the caciques were thrilled to hear that there might be a new admiral, for the Indians were “much aggrieved by the admiral’s slaughters and the gold tribute he had imposed upon them.” Because of this, “there were large gatherings of Indian chiefs” who “discussed the benefits that might result from a new admiral since the old one so mistreated them.” (History, Book I, Ch. 107, p. 57-8)

Petrone’s article also leaves out some important incidents that may be used to judge against Columbus’s legacy, as described in raw detail by Cuneo’s letter to his friend. One such incident occurred after the skirmish with the Caribs early in voyage two. Upon subduing the belligerents and decapitating one with an axe (despite Petrone’s claim that they were all sent back to Spain), Cuneo was given a captive woman to rape. In a famous passage, he writes:

“I captured a very beautiful Carib woman, whom the said Lord Admiral gave to me, and with whom, having taken her into my cabin, she being naked according to their custom, I conceived desire to take pleasure. I wanted to put my desire into execution but she did not want it and treated me with her finger nails in such a manner that I wished I had never begun. But seeing that, (to tell you the end of it all), I took a rope and thrashed her well, for which she raised such unheard of screams that you would not have believed your ears. Finally we came to an agreement in such manner that I can tell you that she seemed to have been brought up in a school of harlots.”

Much has been made of this incident from those on all sides of the spectrum. In 2019, when a debate raged over whether the University of Notre Dame should cover a mural of Columbus, Geography professor (who taught at a different school, showing the extent of this debate) tried to dismiss the incident by saying that since the word “rape” was never used, it wasn’t rape. It is clear to any objective observer that this was not a consensual encounter.

Another incident alluded to above but described in more detail by Cuneo is the capture of 1600 Taíno Indians to subdue the insurrection, with 500 of them being sent back as slaves. Cuneo presents a lurid description of this, complete with evidence that Columbus allowed the men to take slaves for themselves:

“When our caravels were ready to depart for Spain . . . we gathered at our settlement 1,600 Indians, male and female; we loaded 550 of the best – both men and women – . . . on 17 February 1495. Regarding the rest, it was declared that whoever wanted some of them could take them as he wished, and so it was. When everyone was supplied, approximately 400 still remained who were permitted to go wherever they liked. Among those were many females with nursing infants, who, so as to better escape us, . . . abandoned their children to their fate. . . . Among the captives was one of their kings . . . It was decided that they should be executed with arrows . . . but that night they were so adept that they escaped.”

The taking of slaves in this instance is corroborated by Las Casas, who mentions Antonio de Torres sailing back to Castile with 500 slaves, (History, Book 1, Ch. 107, p. 56) and Ferdinand Columbus who states that “though he could not apprehend the cacique, some of his people were seized and set prisoners to Castile” in a fleet that left February 24th, 1495, commanded by de Torres. According to Cuneo, this incident set off alarm bells with the friendly cacique, Guacanagarí, who reported it to his superior Caonabó. The taking of slaves was not foreign to the people of the Americas, but it may have been that they had not seen it on the scale that was familiar to Europeans and Africans.

While these egregious incidents are omitted from Petrone’s article, a more nuanced error shows his amateurism in the domain of historical thinking. He claims that after suppressing the “cannibal rebellion” the grateful Indians were so happy that they showed Columbus where the copper, gemstones, cinnamon, and ginger were. While the claim itself is highly distorted from the original passage in Ferdinand Columbus’s book, there’s another problem with the claim: cinnamon and ginger are not native to the Americas, and were not known there prior to the Columbian Exchange. The book relies heavily on Christopher Columbus’s lost log of the second voyage, and it’s important to consider that from his perspective, he thought he had found Asia. Therefore, he’s applying his schema erroneously to what he sees on these islands; had he known this was not Asia, he may have questioned more thoroughly what these spices were. Petrone does not stop to consider this as a historian would, and instead takes it at face value and passes it along as fact.

There are numerous other examples of Petrone’s distorting and sanitizing the narrative, and omitting information in order to prove his argument about Columbus. But for sake of brevity, we will end it here. I do encourage those interested to go through and check the primary source record against his claims, as I’ve provided links to some of the main sources.

Columbus as a villain: Hans Koning, Howard Zinn, and those who follow

Since the anti-war movement of the 1970s, and more recently the backlash against “traditional” histories in the interest of social justice and inclusivity, the general perception of Columbus has turned overwhelmingly negative, with the most ardent detractors putting him on par with Hitler and claiming he’s guilty of genocide. Even though there’s usually some truth to every historical narrative, many of the most egregious atrocities alleged to have been committed by Columbus are false or exaggerated; their proponents employ similar distortions, omissions, and manipulations of the evidence as we saw with Petrone.

A common source of such allegations is Howard Zinn’s A People’s History of the United States – a polemic purporting to offer a “real” history – which has captured the hearts and minds of millions. Yet throughout the book, Zinn shows a calculated propensity to cherry-pick information, ignore others, manipulate quotes, and offer baseless claims as fact to create a narrative that is more conspiracy theory than reality, with the purpose of instilling ire towards the Capitalist system. To compound this, Zinn forgoes the use of footnotes for citations, claiming it would make the book sloppy. Consequently, it is difficult to check his sources and validate his claims – likely the way he wanted it given how egregiously many of them are misrepresented. Even though many have pointed out the innumerable flaws of the book,6 it still has a large following and a website with resources for educators.

While this section will focus primarily on Zinn’s book, it’s important first to acknowledge the work of Hans Koning, a journalist and anti-war activist in the 1960s and 70s. Zinn was highly influenced by Koning’s book Columbus: His Enterprise, and since much of the information on Columbus in A People’s History bears resemblance to Koning’s,7 we won’t spend much time on him.

But there is one striking example of presentism stemming from lack of contextualization that I will point out. On pages 83-84, Koning writes, “The Columbus brothers now set out to extend their dominion over the entire island and to see to the ‘pacification’ of the Indians. This word has become familiar to us from our Vietnam War, and was already in use then with the same hidden meaning.” While the word was used in situations when there was revolt or insurrection in the Indies, it is faulty to claim that a word written almost 500 years prior and translated from Spanish has the same connotation as it did in the Vietnam war – the violent takeover of small villages which potentially had insurgents. In Ferdinand Columbus’s book, the word “pacify” meant to bring about peace to a region, which could involve violent suppression or negotiated settlement. In fact, the word is used in reference to Roldán’s revolt on voyage three, which ended in compromise between him and the Admiral.

Zinn’s own chicanery regarding Columbus starts in the first paragraph of his book with a famous, often repeated quote that does not actually exist in Columbus’s log. Over and over, Zinn employs creative use of ellipses to more or less manufacture quotes that are not in the original source. It is important to remember that the purpose of an ellipsis in a quote is to shorten it by removing unnecessary wording, but it should not change the meaning. Here’s the quote as presented, which Zinn claims is from Columbus’s log:

“They . . . brought us parrots and balls of cotton and spears and many other things, which they exchanged for the glass beads and hawks’ bells. They willingly traded everything they owned. . . . They were well-built, with good bodies and handsome features. . .. They do not bear arms, and do not know them, for I showed them a sword, they took it by the edge and cut themselves out of ignorance. They have no iron. Their spears are made of cane. . . . They would make fine servants. . .. With fifty men we could subjugate them all and make them do whatever we want.” (A People’s History, p. 1, The two sets of ellipses that are underlined were done so by me)

When read as such, it sounds like an indictment of Columbus’s desire to forcibly enslave Indians, which is what Zinn wants you to believe. However, the two underlined sets of ellipses leave out significant chunks of the original source, including some important context. Here’s the full paragraph surrounding the sets of underlined ellipses, as it’s presented in Diario (p. 67-69):

“They have no iron. Their javelins are shafts without iron and some of them have at the end a fish tooth and others of other things. All of them alike are of good-sized stature and carry themselves well. I saw some who had marks of wounds on their bodies and I made signs to them asking what they were; and they showed me how people from other islands nearby came there and tried to take them, and how they defended themselves; and I believed and believe that they come here from tierra firma to take them captive. They should be good and intelligent servants, for I see that they say very quickly everything that is said to them; and I believe that they would become Christians very easily, for it seemed to me they had no religion.”

Notice that Zinn left out the whole part about the wounds on their bodies and the natives defending themselves, as this would undermine his persistent claims of the Indians being peaceful, proto-Communists. And when taken in context, he’s likely referring to servants of the crown of Castile, as those lands would become part of the Spanish Empire. Had he meant to make them slaves, he would have likely said so, as he used the Spanish word “esclavos” (literally “slaves”) in his 1493 letter to St. Angel.

The second underlined ellipsis in this quote is even more egregious, omitting three pages of the log and written three days later. Here’s the relevant part of the passage:

“And I saw a piece of land formed like an island, although it was not one, on which there were six houses. This piece of land might in two days be cut off to make an island, although I do not see this to be necessary since these people are very naive about weapons, as Your Highnesses will see from the seven that I caused to be taken in order to carry them away to you and to learn our language and to return them. Except that, whenever Your Highnesses may command, all of them can be taken to Castile or held captive in this same island; because with 50 men all of them could be held in subjection and can be made to do whatever one might wish.” (Diario, p. 75-77)

Keep in mind that the log was written to be presented to the king and queen, and in this passage, he’s asking them what they want him to do. An argument can certainly be made that Columbus has ill intentions, but this is a separate matter. The statements about making “fine servants” and subjugating them with 50 men are not related in the original source, but Zinn presents them as if they are. Even the most ardent Columbus detractors have to acknowledge that this use of ellipses to assemble a supposedly contiguous quote from such disparate statements is unacceptable, especially for a trained historian.

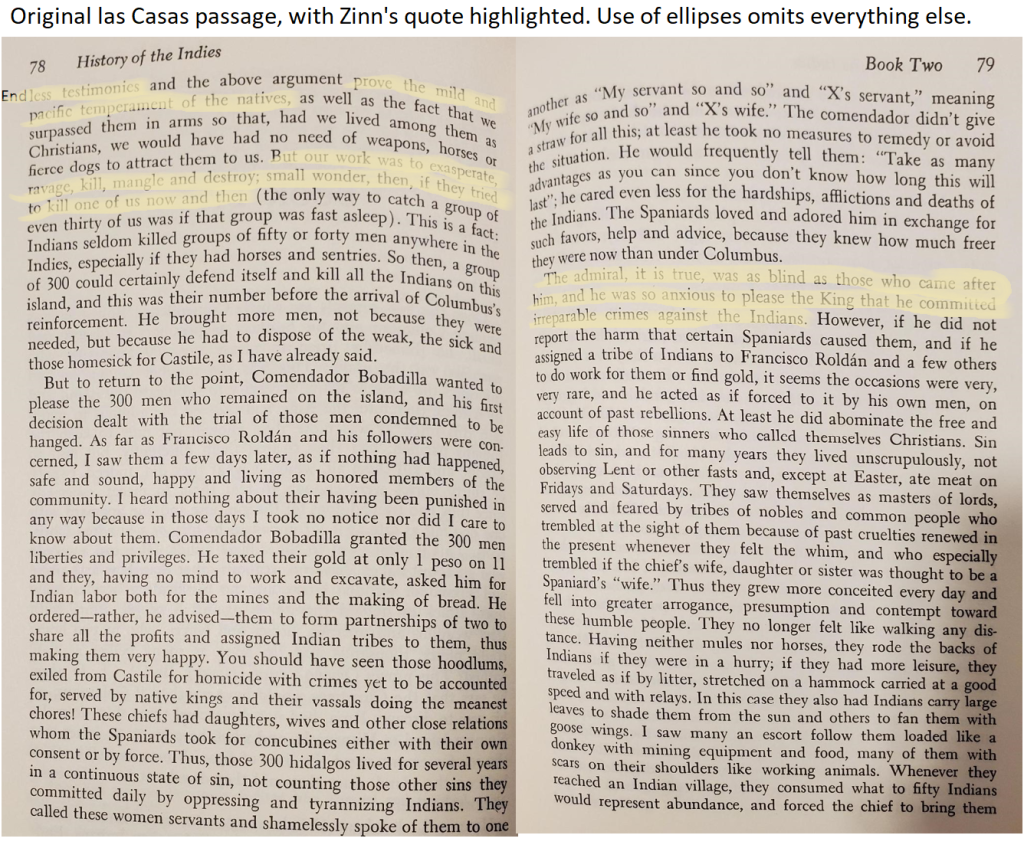

Zinn uses this tactic again on page 6, when he takes a heavily-manipulated quote from Las Casas:

“Endless testimonies . . . prove the mild and pacific temperament of the natives. . . . But our work was to exasperate, ravage, kill, mangle and destroy; small wonder, then, if they tried to kill one of us now and then. . . . The admiral, it is true, was blind as those who came after him, and he was so anxious to please the King that he committed irreparable crimes against the Indians. . . .“

As before, the underlined sets of ellipses omit large amounts of information paramount to understanding what Las Casas was writing. The ellipsis leaves out a full page of the book, in which Las Casas first indicts Columbus for sending unnecessary reinforcements to Hispaniola, but then details in length how conditions for the Indians under subsequent governors was worse. Here’s the last piece of Zinn’s quote in its full context:

“[Bodadilla] would frequently tell [the Spaniards]: ‘Take as many advantages [upon the Indians] as you can since you don’t know how long this will last’; he cared even less for the hardships, afflictions and deaths of the Indians. The Spaniards loved and adored him in exchange for such favors, help and advice, because they knew how much freer they were now than under Columbus.

The admiral, it is true, was as blind as those who came after him, and he was so anxious to please the King that he committed irreparable crimes against the Indians. However, if he did not report the harm that certain Spaniards caused them, and if he assigned a tribe of Indians to Francisco Roldán and a few others to do work for them or find gold, it seems the occasions were very, very rare, and he acted as if forced to it by his own men, on account of past rebellions. At least he did abominate the free and easy life of those sinners who called themselves Christians.” (History, Book II, Ch. 1, p. 79)

In this case, Zinn’s dishonest use of an ellipsis changes the meaning of Las Casas’s words from what was originally a mix of criticism and defense of Columbus into a wholesale condemnation of him. To further drive this point home, I have included the original passage from the book and highlighted the sentences used in Zinn’s quote. Read the two pages in full, then read only the highlighted sections. It is obvious that the original meaning was significantly altered by Zinn.

Such quotes have even infiltrated and inspired some textbooks. Page 27 of History of the United States (McDougal-Littell, 1997) states, “On his first voyage, Columbus had kidnapped several Taino Indians to take to Spain. He had already decided that the Indians ‘should make good servants’ for they were ‘meek and without knowledge of evil. . . .’ ” We’ve already seen the context for the statement about making good servants (written in the October 11th log entry), but the second part of that quote was written a month later on November 12th. In this passage (I bolded the statement), Columbus said that he wanted to take some natives back to Spain so “that they might learn our language so as to know what there is in the country, and that in returning they may speak the language of the Christians and take our customs and the things of the Faith, ‘Because I see and know [says the Admiral] that this people have no sect whatever nor are they idolaters, but very meek and without knowing evil, or killing others or capturing them and without arms, and so timorous that a hundred of them flee from one of our people . . . So that your Highnesses must resolve to make them Christians.” (Christopher Columbus: his life, his work, his remains, by John Boyd Thatcher, p. 563) Again, we see two disparate quotes (in this case, written a month apart) being falsely presented as a coherent thought. And it’s clear in context that the second statement was referring converting the Indians to Christianity as opposed to making them slaves.

Central to Zinn’s narrative is the charge that taking slaves for profit was a high priority – right up there with finding gold. One piece of evidence Zinn cites is Columbus’s 1493 letter to Luis de St. Angel, where he promises to the monarchs “as much gold as they need . . . and as many slaves as they ask.” (A People’s History, p. 3) However, these are only two items mentioned out of a long list, which includes spices, cotton, gum, and “many other things of value” that will be discovered by the men in Navidad. When the whole body of primary source evidence is examined, slaves were no more important than gum or cotton as commodities used to convince the monarchs to fund subsequent expeditions, and they are rarely mentioned by Columbus as a source of profit. Let us also not forget Mann’s statement about just how common slavery was in Europe and Africa at the time. This doesn’t stop Zinn from echoing Koning’s claims that the shipment of 500 slaves to Castile under de Torres and the implementation of the tribute system were executed purely out of need to pay “dividends” to the investors in the absence of large quantities of gold. As we’ve seen to the contrary, these were methods (albeit, arguably harsh ones) implemented as tools for putting down revolts and discouraging future insurrections, a point not mentioned by either Koning or Zinn.

One final claim (originating with Koning) in A People’s History that begs to be addressed is that according to Zinn, the Indians who failed to pay the tribute “had their hands cut off and bled to death.” (A People’s History, p. 4) This idea has permeated countless articles about Columbus and is one of the most recited arguments against his legacy. But there’s a problem: no evidence exists in the historical record to back this up. It is true there was a tribute system and that those who didn’t pay were punished, but Ferdinand Columbus doesn’t say what the punishment was. (The Life, p. 150) Given that this was put in place to keep discipline and suppress rebellion, it’s highly unlikely Columbus would have implemented such a harsh punishment, as that would’ve resulted in renewed discontent.

As it turns out, like some of the other alleged atrocities, this is something that happened frequently in the times after Columbus was governor, but has been erroneously attributed to him. The first mention of such an atrocity by Las Casas comes in Book II, Chapter 15 of History of The Indies which describes the aftermath of a battle in which the Spanish and some Indian allies put down a rebellion from another tribe on Hispaniola:

“After the arbalast attack, Indians could only try to run back to their . . . villages, but . . . the Spaniards overcame them in no time. . . . some Indians were caught alive and were tortured incredibly to find out where people were hidden . . . The Spanish squadrons arrived in this way . . . and you should have seen how they worked their swords on those naked bodies, sparing no one! After such devastation, they set out to catch the fugitives and, catching them, had them place their hand on a board and slashed it off with the sword, and on to the other hand, which they butchered, sometimes leaving the skin dangling; . . . And the poor Indians howling and crying and bleeding to death, not knowing where to find their people, their wounds untended, fell shortly thereafter and died abandoned.” (History, Book II, Ch. 15, p. 117-8)

According to David Marley (Wars of the Americas, pg. 7), this battle occurred between June 1503 and Spring 1504 when Nicolás de Ovando was governor. It’s important to note that Columbus was undertaking his fourth voyage and was stranded on Jamaica at the time. He would make a brief visit to Hispaniola in August, 1504 before heading back to Spain.

For more about this specific claim, I have published a new article (September 2024) which comprehensively studies what the historical record says, as well as tracing the origin of this claim to the present. The article is here: Columbus and the Myth of Severed Hands.

Despite the significant flaws in Zinn’s account (of which there are many others, but I don’t intend this to be a line-by-line refutation), his history has gained a noticeable following in the world of Social Studies education. Many organizations have dedicated themselves to developing curricula aimed at teaching students the problematic narratives in A People’s History as undeniable truth. Time and time again, these have repeated the false and misleading claims of Zinn and Koning.

An examination of one such curriculum, ironically-named “You’ve Been Lied To: The REAL Christopher Columbus”, shows a doubling-down of the claim about Columbus cutting off hands. This time, it is accompanied by an engraving, a quote from Las Casas, and a caption reading “Christopher Columbus’ Soldiers Chop the Hands off of Arawak Indians Who Failed to Meet the Mining Quota.” As we’ve established previously, the descriptions from Las Casas about these atrocities were describing the state of affairs post Columbus. Furthermore, the engraving was created by Theodor de Bry (1528-1598) and accompanied a passage about Spaniards in South America (1539) under Sebastián de Belalcázar in the 1598 publication of A Brief Account of the Devastation of the Indies.8 Attributing this to Columbus shows that the writers either didn’t research it fully or chose to willfully mislead.

Included too is an article written by Bill Bigelow, co-director of Zinn Education Project, calling for the abolition of Columbus day, which also repeats the false claim of Columbus ordering hands severed. Furthermore, he cites a false claim from author Basil Davidson, who calls Columbus the “father of the slave trade,” since the first license to send African slaves to the Caribbean came in 1501, “during Columbus’s rule.” As mentioned, Columbus was in Spain in 1501, having been replaced as governor by Francisco de Bobadilla. In addition, Bigelow claims that Columbus started the trans-Atlantic slave trade the moment he sent a group of Indians as prisoners of war back to Spain. This is also suspect. What we know as the “trans-Atlantic slave trade” refers to the “Middle Passage,” where European slave traders bought slaves from African slave traders and transported them across the ocean in specially designed slave ships. According to the Gilder Lehrman Institute, a highly reputable organization of American History resources, the trans-Atlantic slave trade began in 1526, two decades after Columbus’s death.

Bigelow’s errors highlight the importance for Social Studies teachers to conduct thorough research on the topic they’re teaching and on the educational resources they find online.

Note: Originally, I erroneously attributed the “You’ve been lied to” curriculum to Bigelow because his article was contained within. He informed me that he had never seen the curriculum before.

Reflection

My wife recently asked me how people can believe such a flawed book like Zinn’s without question. It’s the same reason people believe their textbooks without question: they don’t know any better, and we don’t teach them otherwise. Many Social Studies classrooms instill upon students that history is memorizing, repeating, and discussing an unequivocally true narrative of past events, often contained in their textbooks. They are usually not taught how this history was created, or to question and critique its validity. Therefore, when people learn about a different version of history that elicits a strong, emotional response, they don’t question it – why would they if they never have in the past? This leads to a generation of adults who see history in black and white and fight over which narrative is correct and should be taught in schools. Should students learn from A People’s History or should they learn from the equally misleading conservative counterpart, A Patriot’s History? Few stop to consider that both could be flawed.

If there’s one thing to take away from this, it’s the importance for us as a society and as history educators to engage ourselves and our students in history, not as a discipline focused on the memorization and wholesale adoption of prepackaged narratives, but as a process of discovery that seeks to create new knowledge. I believe that much of the political infighting over ideas such as whether we should or shouldn’t remove statues and what topics should be taught in history classes loses sight of what it really means to do history the way I’ve shown above – the way historians do. In the classroom, this looks like teaching students to formulate historical arguments by weighing evidence of the past from interpreting a variety of primary and secondary sources.9 How else would one discover such gems as Dr. Chanca’s description of one of the first Europeans ever to eat a hot pepper?10 In everyday life, this would include referencing scholarly and primary sources and checking facts instead of believing what we’re told or find on the internet.

When we commit to doing history properly, the discourse shifts away from vitriolic childish tantrums to a rich, thought-provoking dialogue, where the nuances of the past are on full display. We create our own knowledge and are thus able to think more deeply about history and its implications to our modern world. In the debate over whether we should celebrate Columbus Day or not, we find information that would make advocates of both sides uncomfortable. Those who want to keep it will see that they are celebrating a man who took slaves, executed captives, implemented oppressive and unjust policies upon the Indians, allowed captives to be raped,11 and and ruled with an iron fist. On the other hand, those who want to celebrate Indigenous People’s Day must accept the fact that, among those indigenous people, are some who enslaved others, genitally mutilated and executed captives, and practiced human sacrifice.

But this is what I love about history, and why others should too; the fact that it is rarely black and white, and there are few undeniably correct answers leaves it open to deep, fulfilling debate. And when we debate the gray areas of history, we attempt to answer more profound questions. How should we determine who or what is worth celebrating? What do our choices about what we celebrate reveal about us as a society? We can then use that discourse to come together and propel us forward. However, that will never happen if we are always stuck fighting over which history is correct as opposed to thinking about how we study it.

Note: As always, I welcome debate on any part of this article. But if you are to present evidence about Columbus, you must follow three rules: it must come from a primary source or one contemporary to Columbus, you must have access to the source in full, and you need to cite it, as we’ve seen the importance in this article.

If you enjoyed this article, please follow me on X – @historyinfocus_net. I enjoy corresponding with other educators and those interested in history and economics. Also, you can reach me via the contact page. Please let me know what you thought of this article and how you heard about my website! Thank you!

Footnotes

- This practice originated in the region with the Olmecs, between 1600-400 BC.

- Thanks to this user for pointing the way to William Thomas Walsh’s book.

- This figure comes from page 112 of De Orbo Novo by Peter Martyr, a contemporary of Columbus. Ferdinand Columbus himself puts the number at 100,000, (The Life, p. 148-9) a likely exaggeration.

- “Poverty, chastity, obedience” (The Life, p. 301)

- I have confirmed via the original sources that the quotes used are accurate, and I agree with Langley’s analysis.

- Here are some prominent refutations of Zinn’s work:

- Undue Certainty: Where Howard Zinn’s A People’s History Falls Short By Sam Wineburg

- Howard Zinn’s Biased History by Daniel J. Flynn